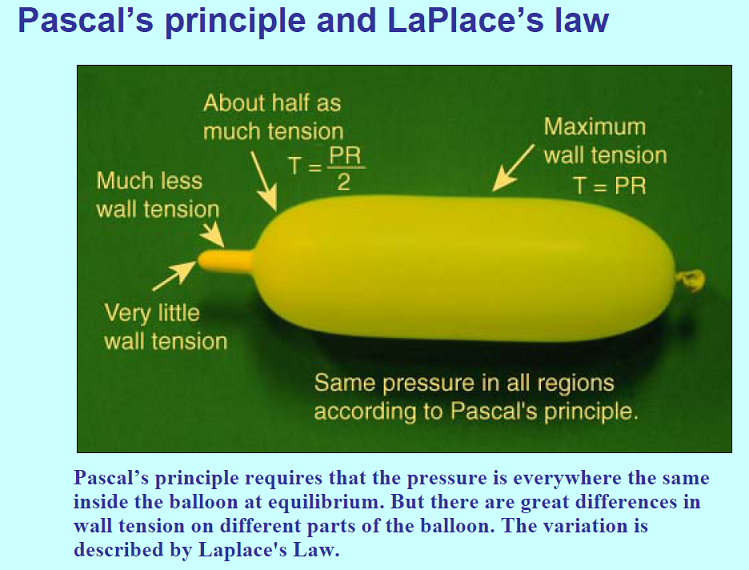

wall tension of the balloon

Posted: Wed Oct 19, 2011 6:43 pm

LaPlace's law has come up before

http://www.thisisms.com/forum/chronic-c ... ml#p154607

but I still don't understand fully. Pressure is the same everywhere inside the balloon. But there are differences in wall tension. At the shoulder of the balloon, wall tension is at half. I don't think I am understanding the difference between wall tension and pressure. The shoulder is gentler on the vein.

Here is some more on this:

http://books.google.com/books?id=pncT2b ... on&f=false

It is important for one to understand the physical principles that govern the effects of balloon dilation. Dilating force is the outward force exerted against a luminal stenosis. It is dependent on balloon diameter, the balloon's inflation pressure, compliance of the balloon material, balloon length, and the degree of the stenosis. The law of Laplace states that the force of tension (T) exerted on the wall of the inflated balloon is directly proportional to the pressure (P) within the balloon and the radius (R) of the balloon (T=PxR). Thus, a balloon with twice the radius of a smaller balloon will exert twice the tension on the wall of a balloon for a given inflation pressure. If the diameter of the balloon is kept constant, the tension on the wall of the balloon will increase linearly with increases in inflation pressure. Because the tension on the balloon wall translates into dilating force, the dilating force generated by a balloon is directly proportional to the balloon's diamter and inflation pressure. Therefore, larger balloons will require less pressure than smaller balloons to generate substantial dilating force. Similarly, larger vessels such as the abdominal aorta or the common iliac arteries will require less pressure to dilate and rupture. The pressure within an angioplasty balloon is universally measured in "atmospheres."

Knowing the balloons in this detail is absolutely not necessary as a patient going for the procedure. But as a TiMSer trying to keep up with the doctors' discussion, it might be necessary....A longer lesion has a larger total area of stenosis than a shorter one does. As a result, the dilating force created by a balloon is greater in a longer lesion. In addition, the dilating force genereated in a lesion is directly proportional to the degree of stenosis for a fixed balloon diameter and inflation pressure. As such, more dilating force will be generated in a tight, high-grade stenosis than in a shallow stenosis. This principle is governed by the so-called clothesline effect. That is, the radial force vector generated by a balloon in a stenosis is greated when the balloon has more of a "waist" on it. This outward force vector decreases as the waist on the balloon diminishes. Therefore, continuing to increase balloon inflation pressure to eliminate a minimal, residual waist will result in relatively small incremental changes in dilating force and is more likely to rupture the balloon. In this setting, low-profile, "high-pressure" balloons offer an advantage over low-pressure balloon catheters. In the past, if a residual waist could not be resolved, the procedure was either terminated or a larger balloon was used. With the use of larger-diameter balloon, more dilating force can be generated, but the risk of rupturing the vessel or creating a dissection "flap" is also increased.

So wall tension is the dilating force, and the dilating force is halved on the shoulder compared to the middle of the balloon.

Pressure is from the inside of the balloon, as a force pressing equally on all parts of the balloon, but up by the shoulder, the radius is diminished, and pressure times radius gives wall tension, thus reducing the wall tension, which is the force that actually pushes against the vein.

High pressure balloons will increase wall tension significantly.

When a high grade stenosis is ballooned, the waist might give way but a low grade or residual stenosis remains. The dilating force is greater against a high grade stenosis than a low grade stenosis. Thus, paradoxically, it might be easier to treat a high grade stenosis than to treat a low grade stenosis. That is interesting, if it is true.

I think this is suggesting that high pressure balloons are of use against residual waisting, and that the benefit of a high pressure balloon is that it creates greater dilating force without going up to a larger balloon, and by eliminating the need to go to a larger balloon size, it eliminates the increase in risk of rupture or dissection that go along with an increase in balloon size. But the high pressure might carry risks of its own. More to come....